The Covid-19 pandemic, which had blocked the planetary economy, underlined the limits of globalization and redefined the interdependencies between countries – especially European ones – with Asian and especially Chinese supply and logistics chains, especially in technology. come to life.

The war in Ukraine and its consequences could be another blow to globalization, challenging this model of international development built since World War II and then accelerated with the fall of the Soviet bloc. This model is based on open markets and free trade.

Globalization, which has contributed to the rise in living standards worldwide, has recently been undermined by the increase in inequalities in the rich countries, particularly driven by the issue of the “winners and losers” of free trade, as explained by economist Dani Rodrick† The war between the United States and China, in the race for economic leadership in the world, also posed a threat to the rules of international cooperation based on win-win. Now the sanctions imposed by the West as part of the Russian invasion of Ukraine may accelerate the process of deglobalization and the creation of new blocs.

International trade is already faltering

Monday evening, Indeed, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has split a study pointing to the risk of “disintegration of the world economy” generated by the war in Ukraine† The organization fears the appearance of multiple blocs that could endanger international trade. Another study published by two economists on March 29 gives a little more substance about this global upheaval and its implications for the well-being of economies (prosperity), with losses estimated at an average of 5% by 2040 and up to 10% in certain regions of the world. In particular, it concerns the return of major customs barriers in the context of the emergence of two blocs around which world trade would be reorganized.

In the short term, the war in Ukraine should already wipe out half of the expected growth in world trade in 2022, i.e. trade between different countries, the WTO estimates. This growth should be between 2.4% and 3%. In October, the WTO forecast a 4.7% increase in world trade. Among the mechanisms the organization unveiled this fall to explain this, the WTO notes that: “to punish” [occidentales, NDLR] direct impact on international flows” and the “change in relative prices (international prices are rising faster than domestic prices, editor’s note) can lead to a redistribution of consumption from traded manufactured goods to services.”

As a result, according to this first WTO study, the crisis is expected to reduce global GDP growth to between 3.1% and 3.7% this year. The OECD, for its part, published an alarming first estimate on March 17. The organization estimates that global economic growth could be more than 1 point lower. At the end of December 2021, the institution expected global GDP growth of 4.5%† This means that this conflict could amputate the global economy by about $800 billion. In the long term, OECD economists warn of a sharp 5% decline in global GDP growth.

Ukraine and Russia: featherweight but essential

According to the analysis of the WTO secretariat, “Most of the suffering and destruction is being felt by the people of Ukraine, but the costs in terms of reduced trade and production are likely to be felt by people around the world due to rising food prices and energy and reduced availability. of goods exported by Russia and Ukraine”.

While Ukraine’s weight in the planetary economy remains relatively limited, its specialization in certain commodities and the collateral damage of the conflict are sending shockwaves across the globalized economy. According to the WTO, in 2019 the two countries distributed about 25% of the world’s wheat, 15% barley and 45% sunflower. Russia alone accounts for 9.4% of world trade in fuels, a share that rises to 20% for natural gas. Moscow and Kiev are also “key input suppliers in industrial value chains”, the WTO says in its report.

Thus, Russia is one of the world’s major suppliers of palladium and rhodium used in the automotive industry, accounting for 26% of the global demand for palladium imports in 2019. Large amount of neon supplied by Ukraine.

Europe will be a region hit by the economic fallout from the Russian invasion, the international organization added, due to its close economic and energy ties with Russia, especially as regards states bordering Moscow or Kiev. According to the WTO report, in 2021 51.5% of total Russian exports went to Europe and 49.2% to Ukraine. Africa and the Middle East are the most vulnerable regions, according to the WTO, as they import more than 50% of their grain needs from Ukraine and Russia.

World trade divided into two watertight blocs tomorrow?

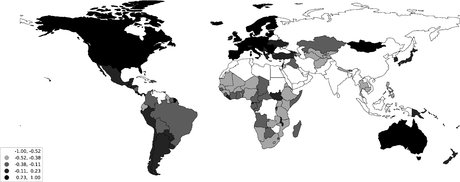

But these immediate effects may well trigger a deeper shift in what is referred to as the “disintegration of the global economy” coined by the WTO. two economists, Eddy Bekkers (WTO) and Carlos Góes (University of San Diego), tried to map out this new global balance that could hold. The authors anticipate a “potential decoupling of the global trading system into two blocs – a US-oriented bloc and a China-oriented bloc”. The geopolitical interests of each country are at the heart of these blocs.

For these two researchers, which are based on the UN Foreign Policy Index, Europe, Canada, Australia, Japan and South Korea would fall into the Western Bloc carried by the United States. Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa fall somewhere in between, with the former being closer to the United States than the latter. India, Russia and most of North Africa and Southeast Asia are approaching China. For its part, the WTO believes: “that there could be more blocs because some countries may find it difficult to belong to one bloc or the other, while others may want to belong to more than one.”

The dynamics already seem to be at work. Russia, as well as Belarus, are now excluded from the principle of reciprocity in free trade with the United States. In this way they join the very closed circle of countries with a revoked trade status, such as Cuba and North Korea. And since the introduction of Western sanctions against Russia, Moscow has increasingly focused on China, where trade between the two countries has exploded since the start of the war. The Chinese Communist Party explained that she was impatient “working with Russia to take Sino-Russian relations to the next level in a new era”† The Kremlin is also increasingly targeting India. This country offers a market for Russian oil boycotted by the western powers, which it sells at an attractive price. This growing movement is not new, economist Jacques Sapir recalled in our columns, who estimated that: “For Russia, the turn to Asia has become essential for its room for maneuver”.

World trade that could rise 160%

Within these future and potential blocs, tariff barriers would remain contained, allowing substantial intra-block trade to be maintained. But according to the authors, trade between blocs could collapse by 98%. And trading costs between rival blocs would rise from 160% in the most pessimistic scenario to a more controlled rise of about 32%. In particular, the rise of customs barriers, but also the disappearance of certain benefits generated by commercial multilateralism, such as economies of scale.

This fragmentation of world trade would lead to a substantial reduction in the well-being of all countries, the two economists note. However, the effects are asymmetrical. While losses would range between -1% and -8% (median: -4%) in the western bloc, they are between -8% and -11% (median: -10.5%) in the Asia bloc, with an estimated real loss of income worldwide of about 5%.

Access to innovation could explain the decline in living standards in Eastern Bloc countries

How to explain such a difference? The ability to innovate is central, the authors emphasize. †By severing ties with richer and more innovative markets, Eastern Bloc countries are reorienting their supply chains towards lower quality products, which in turn leads to less innovation. By contrast, while the Western bloc countries also experience welfare losses, their innovation trajectories seem almost unchanged after decoupling.† And by reducing their innovative capacity, these countries reduce their productivity gains. “So Eastern Bloc countries that currently have lower productivity levels and have more ties to innovative countries have bigger losses,” they project.